Roots of valor

Rukes family has a long tradition of serving our country with pride and patriotism

It’s well known that Brian Rukes, the man behind the RemembER the 44 project, is a teacher at El Reno High School.

There’s a lot of information in his head, especially in regards to World War II, and he loves to share that information with both children and adults. What some may not know, however, is that his father, Charles Rukes, is the same way.

His knowledge spans family history as well as war history, and the two subjects are very closely connected.

Charles fought in Vietnam, so he knows about war. The loss, the sacrifice, the courage — the feel of it.

His connection with the military is deepened even further by the story of his family, especially his uncle, Merlyn Dale Rukes.

Merlyn, usually referred to as Dale, was born in El Reno on May 26, 1920. His parents were Charley Rukes and Pearl Loretta Rukes.

They were later referred to by family as “Grandma and Grandpa Charley.” Like many soldiers in the 44, Dale grew up on multiple farms.

The Rukes family moved around a lot, as they weren’t able to afford owning their own land. They lived in many areas including El Reno and Okarche, as well as at the Filmont Ranch in New Mexico.

During Dale’s school years, he was an athlete who raced in track competitions. His determination throughout his life was coupled with another character trait, one that Brian and Charles can understand without having ever even met him.

“He was someone who was loyal,” said Brian. “He didn’t want to wrong anybody, and he always wanted to do what was right.”

Dale joined the war effort on Jan. 9, 1942. He wanted to be in the Army Air Corps, and he got his wish as a tail gunner in the 358th bomb squadron within the 303rd bomb group.

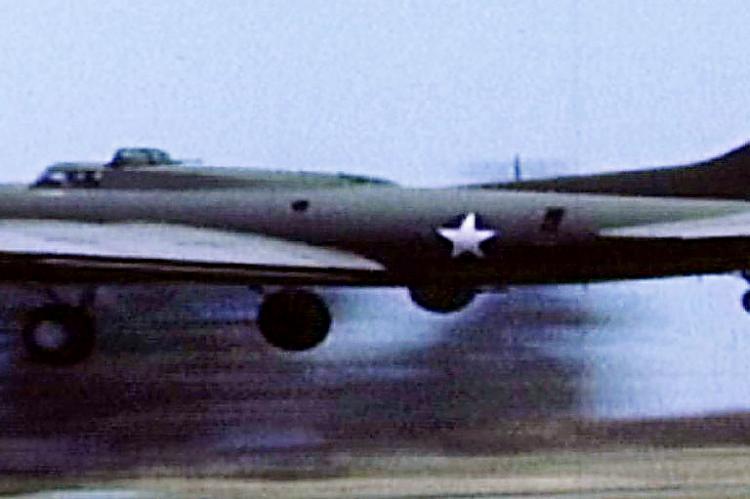

Also known as “Hell’s Angels,” this group of B-17’s was a part of the 8th Air Force.

Back then, there were only four major air bombing groups, referred to as the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. There were less bombers than there were toward the end of the war. It was risky business fighting in WWII, especially in the early years.

“If you were in the Air Corps back then, there was a very high probability that you were going to die,” said Brian.

More bombing groups were added, but the original ones were often outnumbered and outgunned. This was the case during a mission in France on Jan. 3, 1943.

Some of the 303rd were engaged with Germany, bombing Nazi U-boat pens at St. Nazaire. Dale was in his main aircraft, a B-17F bomber known as Leapin Liz. They were hit by anti-aircraft fire, and the plane exploded 15,000 feet in the air, killing the occupants.

Dale was reported missing in action, but there was some initial confusion over what really happened. It was hard to ascertain the circumstances miles into the air, and the fate of the Leapin Liz was uncertain.

Dale’s parents didn’t know what to think. His mother, Pearl, even continued sending him letters. In one of them, sent in February, Pearl questioned how Dale had recently been given a military award while he was MIA.

“You were all over the radio and all the papers again. It came over the radio at 10:15 Saturday night when we heard you were awarded the Oak Leaf Cluster. It nearly shocked us to death. Now, what we would like to know is, where are you? How could they present that award to you if you wasn’t there?”

She had thought that Dale needed to be present to receive the award in London. But this, unfortunately, was not the case — the Air Corps, on Jan. 3, 1944, said that Dale was presumed killed in action.

According to Brian, the soldier’s parents had a hard time accepting the death of their son. When a soldier was serving back then, his family usually displayed a Blue Star flag.

That flag was changed to a Gold Star flag if the soldier’s status was changed to deceased. But Brian said he has never seen a Gold Star flag for Dale, and he believes the family may never have changed it.

“I personally think his parents never wanted to give up hope. They didn’t want to believe he was dead.”

Dale’s death, though unimaginably tragic, also brought his family a bittersweet gift — enough life insurance money to purchase a farm of their own, comprised of 160 acres.

That farm, located near Geary, is still owned by Brian's dad, Charles.

Throughout his career, Dale was decorated numerous times, including medals for five combat missions as well as two clusters for shooting down aircraft. Videos of him and his plane, the Leapin Liz, can be found on YouTube in living color.

Charley Rukes passed away May 26, 1981. That day would have been Dale’s 61st birthday. Charley’s wife, Pearl, passed away May 31, 1983. But before their deaths, their grandson had his own war experience.

In 1969, the nephew Dale never knew, Charles, joined the war effort in Vietnam. He volunteered and said it was the right thing to do.

He also said his grandparents equated his life path with that of Dale, and he had heard stories about his uncle for as long as he could remember. The importance of fighting for our country was taught to him very early.

“It was just what you do,” he said.

One particular moment brought his connection to the service and his family into focus. When Charles returned from the war, his Grandma Pearl thought of her son.

“Dale’s home,” she said.

Charles said that he had grown especially close to his grandparents, partly because of the loss they had suffered in 1943. Brian further explained this connection.

“When my dad was younger, he spent tons of time on the farm with his grandparents. He felt that he belonged there more than he ever did in town.”

“I carried him with me my entire life,” said Charles. “They always put me in Dale’s place.”

Charles spent years learning all he could about his uncle. He’s even kept a few of Dale’s physical artifacts, including 246 letters written by Dale during the war. Some of these letters are especially poignant, especially the final one from Jan. 1, 1943.

“Well, this is the first of a new year,” it said. “Things will be a lot different this one than the last one.”

“He didn’t know what he was saying,” said Brian, as Dale was killed only two days later.

His final letter was received by his family 20 days after his death.

Other items kept by the Rukes family include a foot locker containing a Bible and a shaving kit. Charles took that foot locker to a reunion for the soldiers of the 303rd. A few men recognized it and they wept aloud as they recounted how they had played cards on it with Dale.

Charles, too, becomes emotional when he recalls this event and other details about his family. These feelings can be felt in a way that no one but a military family can comprehend.

Charles’s connection with Dale, war and the United States was passed on to his son. Honoring the memory of fallen heroes is one of Brian’s greatest passions, and he is consumed with enthusiasm and with gratitude every time he discusses it.

“I grew up around this stuff. I know what it means, what it’s like to recognize people who sacrificed for our country.”

The sentiment is echoed by Brian’s father.

“We learn from looking back on the past. We don’t just learn the past, but some of what might be expected in the future. A lot of people paid the price for us to live here.”

Along with 43 other El Reno men, Dale is soon to be honored at an ambitious ceremony, and the history of these soldiers is starting to become public knowledge.

This information was meticulously collected by Brian Rukes in two ways — through the research of historical documents and through contact with the families of the 44. He and his father had done something similar years ago, searching through documents about Dale in Washington, D.C. and Maryland.

Over time, they learned about the men he served with as well. But the information on the other soldiers in the 44 was discovered recently, in El Reno at the Heroes Plaza Memorial.

Brian learned there were six names not included in the original memorial at the high school stadium.

From there, his goal was to create a new memorial with the names of 44 rather than 38. These men had all attended an El Reno school at one time, had served in WWII, and died in the service, even if it was after the war.

Brian said the memorial is of extreme importance to him, the families and El Reno’s children.

“I’ve always appreciated history, especially those who served our country. Their stories absolutely need to be remembered.

“I want my students to learn how to do relevant research. I want them to take pride in El Reno and go on to do great things. I also hope people coming through El Reno will take notice.”

RemembER the 44 is not just about Dale, Brian said. Rather, it’s about every El Reno soldier on the list and they are being honored equally. Even if Dale wasn’t in the picture, Brian said he would still have worked on this project for the sake of the families and for the history he believes should never be forgotten.

“It means so much to families. I feel a connection with families, I hear it in their voice or see it in their eyes. Dale is just one of those 44. The other 43 mattered just as much.”

Along with the other 43, Dale’s legacy lives on through family members. Dale had a brother, Charles DeWayne Rukes, who married LaVerne Crumley. LaVerne still resides in El Reno.

Their only child was Charles, who fathered Brian and William with Kaye Rukes. Kaye passed away in 1993, and Charles remarried. His current wife is Faye Rukes.

Brian is married to Susan Rukes. They have two children, Jonathan (10) and Elisabeth (8). Brian said that, just like him, his kids have heard about Dale their whole lives.

The Memorial Rededication Ceremony will be held the evening of Oct. 4 at Memorial Stadium in Adams Park.